Wulo Exhibition

Some of the presented works

Fluttering Emotions (Installation with sound & wind)

የሚራወጡ ስሜቶች

It is a customary practice in many communities to wear ‘Netela,’ (a traditional fabric) upside-down, during periods of mourning and when attending funerals or visiting mourning houses. Growing up in such a community, I have observed this tradition since my childhood. Like countless other mothers, my own mother also had Netela reserved exclusively for times of mourning. Whenever she returned home from a funeral service or a visit to a mourning house, her first action was always to carefully fold the Netela and place it in the cupboard. Folding the Netela was a shared task. I remember assisting my mother with these ritualistic actions from time to time. The meticulousness and reverence with which they handled the process of folding Netela is truly remarkable.

This act of folding the Netela seems to serve a dual purpose. On one hand, it symbolizes the conclusion of the mourning period and the impending return to normal life. On the other hand, it acts as a preparation for the possibility of future periods of mourning, as no one can predict what tomorrow may bring. In either case, it underscores a fundamental truth: there are moments when the Netela remains unused. While it is undeniable that grief is an intrinsic part of life, the interlude between the most recent mourning and the next one is of paramount importance.

Mourning possesses an inherent temporality in its essence and purpose. The grieving process is, by its very nature, circumscribed by time, or at least it should be. Consequently, aside from affording us the time to launder, fold, and store mourning time clothes—a moment that permits to make peace with past sorrows and appropriate preparation for future ones—it also offers us the opportunity to dream and plan for the days referred to as “tomorrow,” without having sadness and misery as a main accompaniment for our imagination of the future.

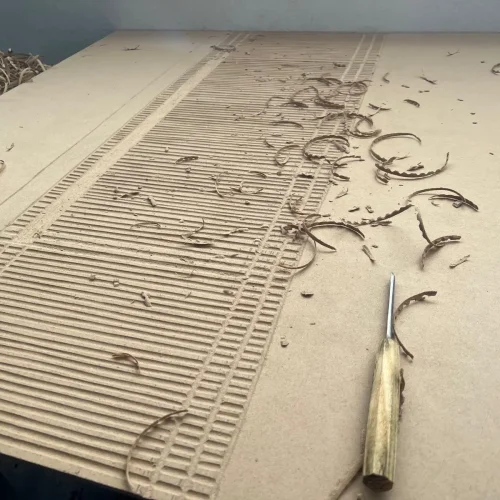

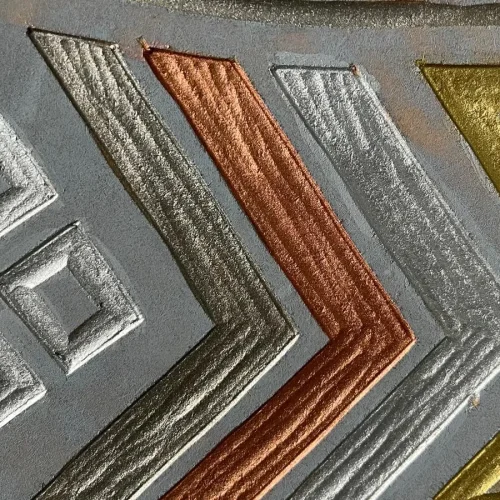

Noise by Choice (Experimental Woodcuts)

እየየ በምርጫ

Should grief be a matter of choice? Take, for instance, our capacity to empathize or withhold it when confronted with the tragedies of others, such as the recent wildfires in Hawaii or the earthquake in Turkey. It might appear that we have the discretion to decide whether or not to be moved by the misfortunes that befall fellow human beings. However, I contend that it is not appropriate to assert that it is our duty as human beings to remain unaffected by the precarious circumstances of others. In a closely-knit community like ours, characterized by deep normative values such as Negbene, failing to empathize with the afflicted and the victim would be a disavowal of our social reality. Nonetheless, the extent to which we should immerse ourselves in the process of empathizing and sharing the experiences of others remains an open question.

Yet, there exists a powerful symbol within our society—the inverted Netela—which signifies a period of mourning. Recognizing the significance of an inverted Netela is essential to provide the emotional and moral support necessary to console and stand with those who are grieving. Our perception of whether a Netela is inverted or not largely depends on our perspective. However, if we fail to discern the presence of the inverted Netela while someone claims to be in mourning, it may be worthwhile to introspect about our own position. Understanding this issue and responding appropriately is not a matter of external proclamation or someone else’s decision. It is a responsibility that rests with each of us individually.

Check; 1… 2… 3… (Installation)

ይሰማል? 1… 2… 3…

One of the vivid childhood memories many of us share is the haunting sound of the ‘Turumba.’ The ‘Turumba’ is a traditional sound instrument employed to announce losses and funeral ceremonies. When a family member passed away, it was customary that the assigned person blow the ‘Tsimamba’ in the neighborhood.

Usually, Turumba is blown between four and five o’clock in the morning, when many people are still in deep sleep. Members of the Edir (traditional funeral and bereavement association) follow the detailed announcement and gather at the residence of the mourners’ house around six in the morning for the mounting of a mourning tent. As a member of Edir, my father did the same. Whenever a loss is announced, my father gets up early in the morning, puts on his Gabi (Traditional fabric), and goes to the house of the mourners to set up the tent with fellow members. This can sometimes happen two or three times a week. But I never once heard him complain about getting up early in the morning and not being able to finish his sleep. This is not only my father’s quality, but also of most people. Following the installation of the mourning tent and attending the funeral ceremony, they go to the mourning house for three consecutive evenings to comfort the family who have lost their loved ones. Mothers also go to the home of the bereaved with food and drinks to comfort the family in grief.

Now that I think about it, it makes me wonder. The deep social tenacity of giving deep and unwavering respect and space to those who are dead and grieving because of the loss—no matter whether those who died suddenly, those who died with sickness, or those who committed suicide. I wonder if this kind of social energy that our parents were able to have with us?

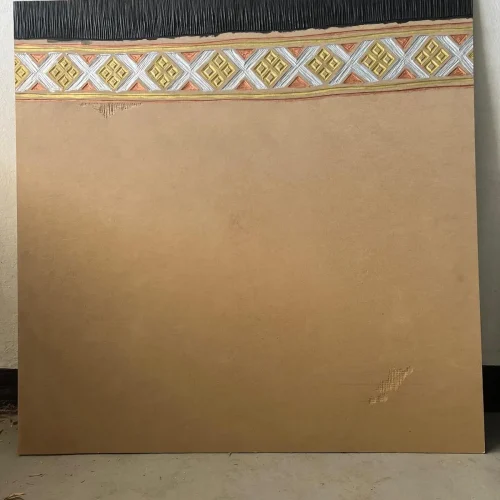

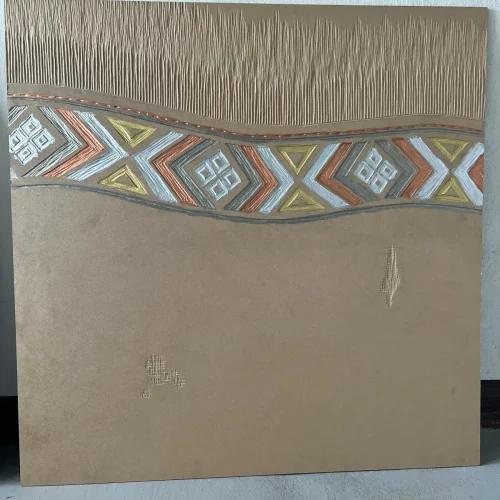

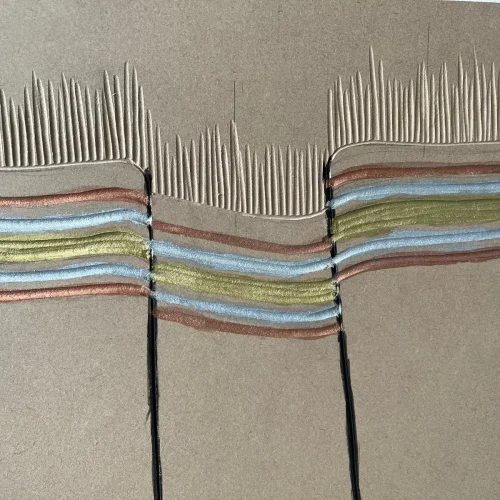

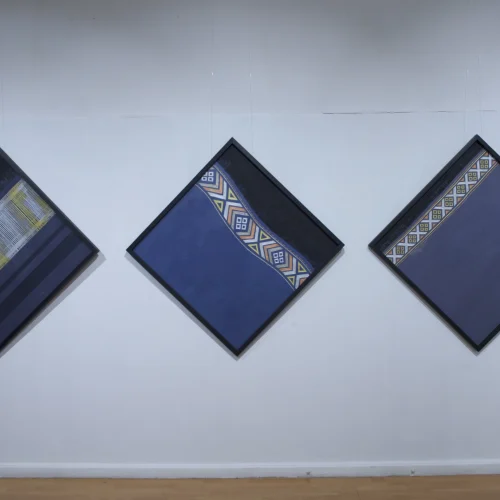

Layers of tomorrow (Mixed media)

በነገ ላይ ነገ

In intricate socio-political and historical contexts, conflict can often emerge not merely as an unavoidable outcome but as a necessary one. The pent-up emotions of anger, indignation, and suppressed grief inevitably seek an outlet through some form of confrontation. Conflict, in fact, constitutes an inherent facet of any social relationship. Could we not consider enmity and discord as integral elements within the spectrum of love? It is within the crucible of conflict that communities must embark on a continuous journey of learning, unlearning, and relearning both tangible and abstract realities, serving as a means to dispel doubt, confusion, anger, and apathy.

The pertinent question lies in discerning the juncture at which conflicts transcend the capacity of individuals and communities to recognize the profound harm violence inflicts on the collective future. It is imperative to explore how singularized indignation can be transmuted into a moral force necessitating collective responsibility and responsiveness.

The absence of accessible platforms conducive to active and careful listening among members of a community can impede the healing process and extend communal grief. This, in turn, fuels conflicts that sow the seeds of active and contagious wounds. Unaddressed wounds, devoid of space for grief and mourning, inevitably carry the potential to solidify into lasting scars, thus perpetuating the cycle of violence. Therefore, it should be a collective duty of communities to collaborate in the healing process in an earnest endeavor to avert the formation of enduring scars.

Before Dawn? (Room Installation)

ከወገግታው በፊት?

As we all know, there is nothing that the modern media does not bring to our ears every day. We hear all kinds of violence, loss, displacement, and death. The fact that we are so used to listening endless stories of death, it feels like people who are loosing their life become just numbers. For sure there was time when one person is a lot already, but not these days. The media tells us numbers, places, and communities. I doubt that I am able to listen and understand those numbers, names of places, areas and sections of society that I hear everyday frequently. There are many indications that this situation is not only a problem for me but also for the larger society. In connection with our failure to meet our social responsibilities and to properly deal with corrupted role of the media, we became unable to listen and understand stories of violence, fear, and death beyond the limiting understanding of kinship. Even with such a single-root understanding of difference and relations, we haven’t been able to share the pain of those who are suffering within different contexts.

The works included in the room installation are arranged to remind ourselves that it is not numbers we are loosing. The places of conflict and displacement that we often hear about in the media are not just names, but are physically located with inhabitants living in fear of violence. I tried to remember those who live in fear of death and those who have already passed away. I hope the audience share those uncertain feelings of loss while interacting with the works composed in the room installation. There are different works of art with various forms and formats included. There are installation with fabrics, textile designs, there are mapping works accompanied with short sentences, sound composition, bodily and sensory experiences, and engaging atmosphere. The body of works are not to be viewed and experienced individually, rather as a whole. I respectfully invite the audience to ponder and digest the energy of the works and the ideas they can convey by an intimate reading.

To create an opportunity to provide additional meanings and experiences, the room is left dark. So as long as viewers are interested in seeing the works up close, it means that they are given the responsibility of creating light in the darkness. To help with this task, flashlights are placed at the entrance to the room.

Still-Life (Photography)

ቁሳቁስ

The term “still-life” refers to a genre of art that portrays motionless objects drawn from both the natural and man-made realms, including items such as fruits, vegetables, flowers, … as well as vessels, baskets, and bowls. A still-life composition captures objects in a state of immobility, frozen in time. Throughout art history, this genre has served as a valuable means for artists to hone their skills in rendering diverse materials, shapes, colors, textures, and lighting, while also exploring the art of arranging objects proportionally within a composition. Notably, after the seventeenth century, the popularity of still-life art surged, a trend closely tied to the process of urbanization and the evolving concepts of home and possessions.

In the realm of photography, a still life can manifest as a carefully curated collection of objects, each laden with specific cultural and historical significance. In the case at hand, the photograph showcases an assembly of items that older generations readily associate with the culinary traditions of mourning, often facilitated through customary mourning associations known as ‘Edir’. It is intriguing, and indeed heartening, to observe how objects can encapsulate collective memories.

These objects may evoke a range of emotions; for some, they may bear the weight of painful memories associated with loss and grief, while for others, they may represent the liberating memories intertwined with the healing process. However, one fact remains unequivocal: These objects, along with the stories and functions, they constitute a crucial part of our shared socio-political conditions through which we should embrace them in our everyday lives.

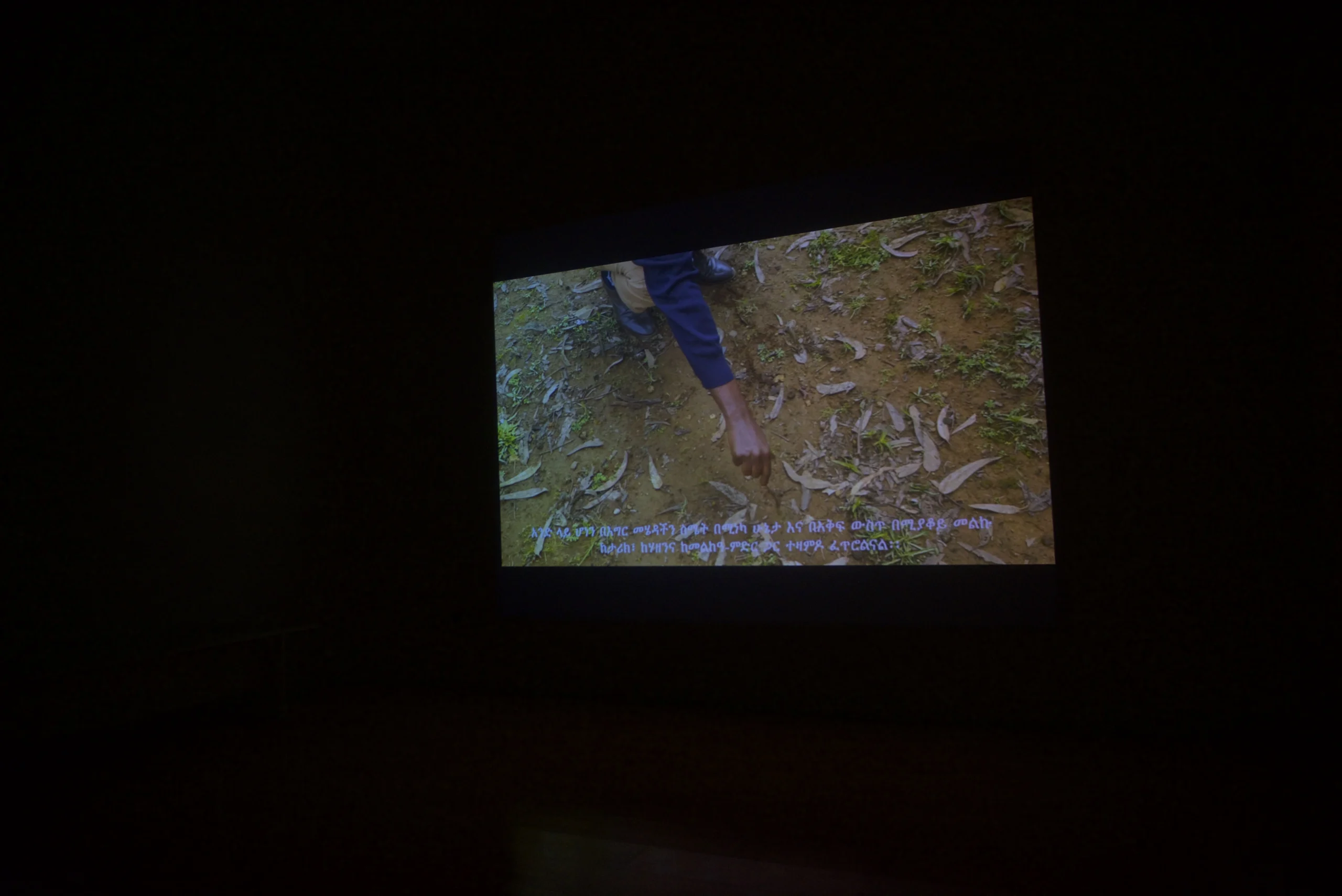

Care and Become (Video, 35’ )

መቆርቆር እና መሆን

“Care and Become” is a two-year artistic research initiative spanning from 2018 to 2020. This project emerged from a profound aspiration to articulate the concept of mourning through diverse aesthetic, pedagogical, and political expressions and methodologies, with a particular emphasis on the exploration of local knowledge and embodied practices.

As an integral facet of this artistic research endeavor centered on the concepts and practices of mourning, I took the initiative to conceptualize and orchestrate a collaborative mourning experiment within Addis Ababa in 2019. This collective mourning experiment actively engaged individuals from different creative disciplines, experiences, and cultural backgrounds, all converging for a span of six intensive days. In this unique gathering, we engaged with a wide spectrum of activities and encounters set against the backdrop of the urban landscape. These activities were rooted in mourning traditions, enabling us to activate our senses and engage our bodies and minds differently. We repeatedly encouraged ourselves to delve into the visceral aspects of our experiences.

The video projected in the room serves as a comprehensive documentation of the diverse experiments and practices that unfolded during our collective engagement. The video is accompanied by narration and sub-titles to guide viewers through the contents, contexts and practices of our collective entanglements with mourning.

Response-ability? (Installation, Video, Woodcuts)

… እምባ አይገድም?

As many of us remember, in March 2019, an Ethiopian Airlines Boeing 737 MAX 8 crashed shortly after take-off from Addis Ababa. The remote location of the crash was near a small village where poor farmer families live. One year later, some of the families and friends of the deceased passengers visited the crash site to place flowers, finding that the residents of the nearby village had already gathered to perform an annual ritual to honor those who perished. Despite being strangers to the victims, the poor farmer villagers performed timely mourning rituals throughout the year, dedicating their time, energy, and meager resources to honor the lost lives of strangers. What does that mean for our ongoing understanding of loss, care, and the precarious conditions of one another?

Traditional communities across diverse contexts have a profound understanding of mourning that extends beyond human experiences of loss to encompass non-human entities, nature, and the land. They have honed the art of cultivating and nurturing respectful relations with non-human animals and the natural world. There exists a deep-rooted belief in the kinship between humans and their domestic animals, often regarding them as cherished members of the family. Remarkably, even during the dire times of famine in the 1980s, families would endure hunger rather than contemplate the slaughter of their cattle for the sole purpose of sustaining human lives. Where are our cattle now?

We had communities that upheld enduring traditions for appropriately grieving the losses of non-human entities and nature. I can vividly recall moments from childhood when I observed elderly individuals responding to the demise of non-human elements. In the vicinity of my neighborhood, there was a road leading to a rural area, intersecting with the city. Farmers from nearby rural areas would traverse this route on specific market days of the week to buy and sell their goods. Whenever they encountered a fallen branch of a tree on their way, they usually picked them up from the road and tenderly placed them beneath a tree. At that time, I did not fully comprehend the significance of this ritual or action, nor did I question it. However, I now understand that it was an act of care and mourning for the loss of the tree, reflecting an individual’s role as both a witness and an active participant in fostering interdependent and respectful relationships. Aren’t those leaves and branches on the table now?

Whose life is grievable? Whose life is disposable?