The taste of water

Leaky vessels, flowing rituals, and non-consensual collaborations

9.11.2022–5.3.2023

Exhibit Gallery (Academy of Fine Arts Vienna)

Vienna

© Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

Photo: Simon Veres

Water. Water has memory. It registers what happens to it. It seems simple and pure but it hides its dissolved memories in plain sight – histories of labor, pollution and colonialism. Its flow conjures connnections of discontinuous times of experience. Water is centrifugal and fugitive, it is in/around/within/without/below/along. Water leaks through territories. Moving through pores, bodies, communities and nations – water loves and conflicts. Water is an element of care in a time when land is the element of fear. Water is also a weapon, a conflict line, a surface that reflects geopolitics and shapes economies and climates. It is both a resource and a proxy, a venue for constant „friction“ at the crossing of empires. The Taste of Water is a site for multiple encounters with and around water. The exhibition is a leaky vessel, with artworks flowing in and out of the space. Propositions are realized elsewhere only to wash up on the Academy’s shores. As an exhibition, performance space, screening room, and ritual space, The Taste of Water takes cues from water’s characteristics – flowing, shape-shifting, non-linear – appearing as a medium and signifier, in the shape of sensorial sculpture, sound installation, video work and text interventions. Like the gravitational phenomena of rising and falling of tides, at times, the currents meet or diverge, forming a venue for non-consensual collaboration, swimming in mud, a place of sharing rituals, and olfactory

witchcraft.

An exhibition by the PhD in Practice program of the Academy with works by: Mohamed Abdelkarim, Andrea Ancira, Angela Anderson, Anca Benera and Arnold Estefan, Berhanu Ashagrie Deribew, Soñ Gweha, Masimba Hwati, Hyo Lee, Rabbya Naseer, Vrishali Purandare, Francis Whorrall-Campbell

As my feet touches the muddy ground, …

The riverside is always muddy, … she said. It registers the footsteps of humans and nonhuman animals who visited the river—never gets tired. With the dark brown color of the soil and all the footsteps on it, the riverside looks lumpy but remains soft when you find yourself on it.

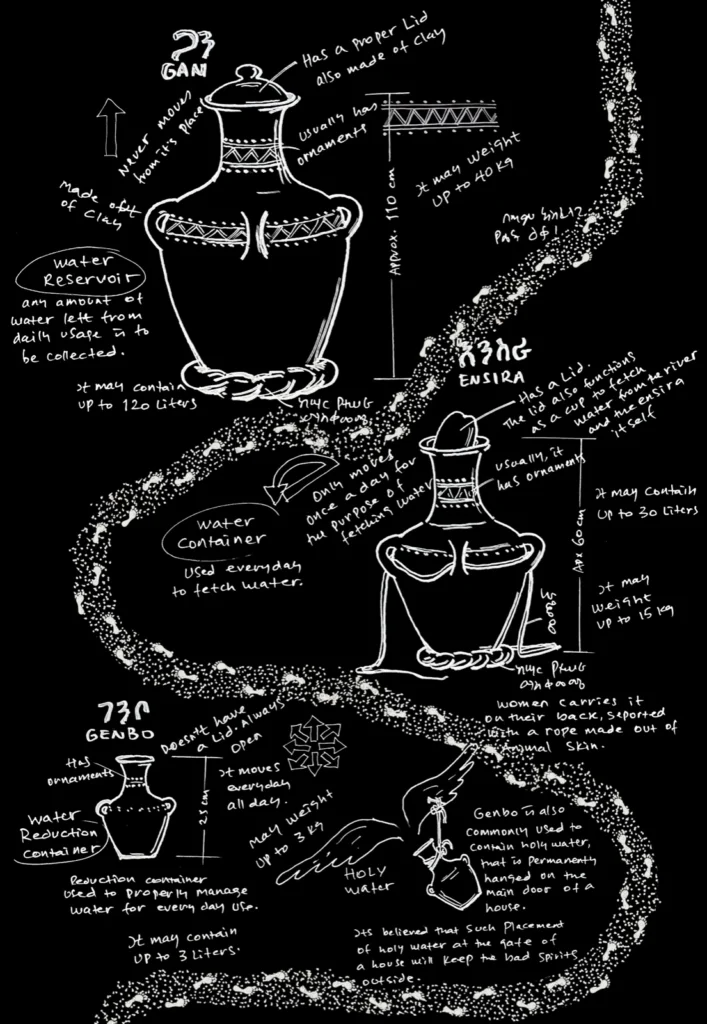

She continued, … I go to the river every day to fetch water. To reach the river, it takes at least two hours of walking from our village. It is neither fun nor safe to walk that far alone—every single day. So, we always go to the river in group. You know, every one of us wants an allay in such a long journey that we have to make every day. Each morning, after feeding breakfast to the family and deploying the cattle for grazing, we go out with our Ensiras (a water container made out of clay) on our backs to fetch water for daily cooking and cleaning activities.

After walking on dry landscape for hours, as we are getting close to the river, we first encounter different smell of the air. The smell is hard to describe, … it smells like, I would say, …. a new day! … The closer we get; we start to hear the sound of the river flowing gracefully on the river bed. The sound is, somehow, similar to listening to rain from inside a thatched roof house. … Right before we approach the river, the muddy ground by the riverside welcomes us. When my feet touches the muddy ground, … I feel … eternal. My presence in the muddy area makes me an active witness to the intimate relationship between water and soil. The presence of mud is a sign that confirms we are still in good hands. Yet, . … we don’t know how long that lasts. The amount of water in the river is getting less and less these days.

Every year in the fall, the community gathers by the riverside to show gratitude to the spirit of the river. We usually start preparing weeks before the actual day of the ritual. We gather and discuss how we can make the ritual-making ceremony better than last year and the year before. Women are usually more active in the process of organizing the annual ritual ceremony—it has been like that for centuries. We believe it is crucial to maintain such spiritual relationship with water. That way we can protect the river, as well as the women in our village, from being over-exploited than they already have.

Ritual ceremonies are very well attended—always full of joy with colorful dresses, songs, dances, prayers and blessings. It always passes quickly. The next day, like any other day, we go to the river to fetch water. The first thing I always notice as I reached the river is the endless number of footsteps recorded on the muddy ground. Usually, footsteps on the ground have a pattern—somehow to and from the direction of the river. But the days after the ritual gatherings, the muddy ground holds footsteps with multiple layers and directions. A large number of footsteps hold water on their molds that generate multiple tiny ponds in the area. Those tiny ponds are just traces of our collective presence and intention to maintain respectful relations with the river. It always gives me joy to witness those multiple footsteps and the water on their molds—so far, … muddy water.